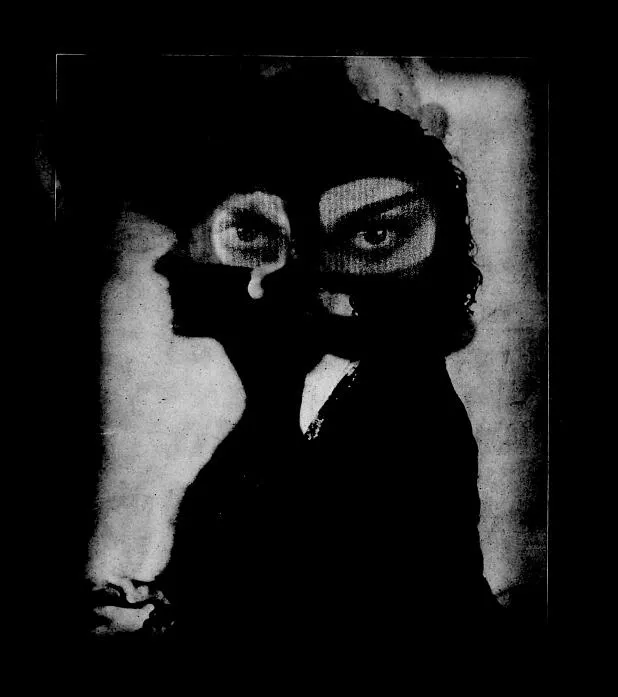

A stark psychological study of the incel as a product of modern alienation, cultural violence, and the fractured shadow self buried within contemporary man.

Read next

The Domestication Of The Modern Man

The Domestication of the Modern Man dissects how stability-driven systems quietly narrow autonomy, intensity, and self-direction without force, without collapse. A precise anatomy of how predictability replaces vitality in contemporary life.

A Message on Survival, Loss, and Hope

This piece confronts mental health stigma, grief, and the reality behind suicide statistics, calling for open conversation and compassion. A message of resilience and hope, reminding anyone struggling that help exists and survival is possible.