This essay explores how the fall of Newtonian physics and the rise of Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics transformed our understanding of scientific truth, revealing that no theory is ever final.

Over the last few decades, reflection on the nature of scientific knowledge has been quite lively. The readings of science proposed by philosophers, from Carnap to Bachelard, from Popper and Kuhn to Feyerabend, Lakatos, Quine and van Frassen, and many others, have transformed our understanding of the nature of scientific activity.

To a considerable extent, these reflections were a reaction to a shock: the unexpected collapse of Newtonian physics at the beginning of the 20th century.

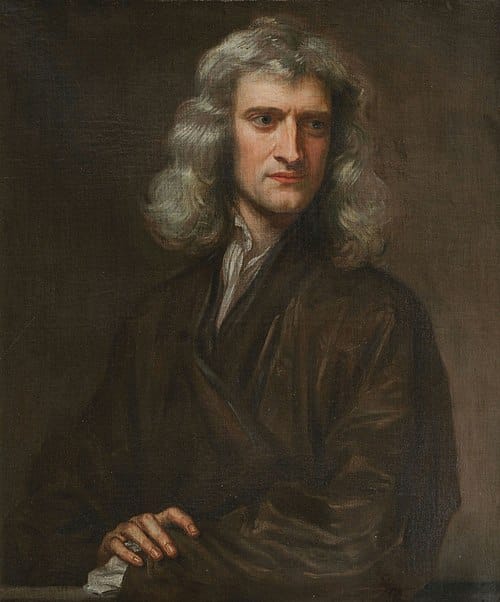

In the 19th century, it was commonly said that Isaac Newton was not only one of the most intelligent men humanity had ever produced, but also the luckiest, since it was still believed that there was only one set of fundamental laws of nature, and he, Isaac Newton, was the lucky one to have discovered them. Today we know that this idea is profoundly flawed and reveals a serious epistemological error: the idea that good scientific theories are definitive and remain valid forever.

The 20th century shattered this illusion. Careful experiments showed that Newton's theory was inaccurate. Mercury, for example, does not move according to Newtonian laws. Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg, and their colleagues discovered a new set of fundamental laws—general relativity and quantum mechanics—that replace Newton's laws and work well even where Newton's theory fails: for example, in explaining the orbit of Mercury or the behavior of electrons in atoms.

However, scientists agree that even the new laws discovered by Einstein and Heisenberg will be replaced by even better ones. Indeed, the limitations of the new theories have already become apparent. There are subtle incompatibilities between Einstein's and Heisenberg's theories that make it unreasonable to think we've reached the definitive laws of the universe.

Now, the key point is that Einstein and Heisenberg's theories are not minor corrections to Newton's theory, but rather a radical rethinking of the world. According to Newton, the world is a vast empty space in which particles move like pebbles. Einstein understood that this empty space can bend, curve, and, in the case of black holes, shatter.

Quantum physicists, for their part, understand that Newton's particles are not particles at all, but rather hybrids between particles and waves that move on Faraday's web.

So, during the 20th century it was discovered that the structure of the world is profoundly different from how Newton had imagined it.

On the one hand, these discoveries confirm the cognitive capacity of science. As with the discoveries of Newton and Maxwell, they too rapidly led to the impressive development of a new technology, which radically changed our society. Faraday and Maxwell's ideas were followed by radio and all communications technology. Einstein and Heisenberg's ideas were followed by computers, information technology, atomic energy, and countless other technological advances that have transformed our lives.

On the other hand, the discovery that Newton's picture of the world was inaccurate was disconcerting. After Newton, people believed they had definitively understood how the basic structure of the physical world works. This naive belief has proven wrong. Furthermore, the pictures of the world constructed by Einstein, Heisenberg, and their colleagues will likely also prove inaccurate.

Support independent philosophy and culture and get access to exclusive unique essays, events and workshops.

Join the movement - THELIFTEDVEIL Global Creative Media Institution

References

Che cos'è la scienza. La rivoluzione di Anassimandro by Carlo Rovelli (First published: 2017)

Comments ()