The Last Man: Camus’ Absurdism in the Penalty Box

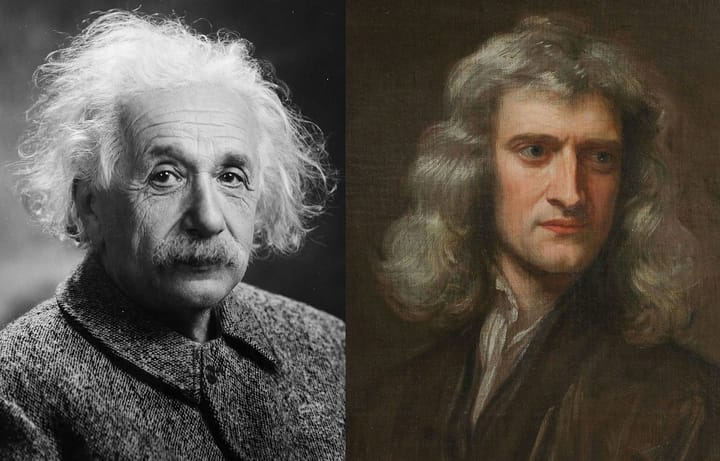

Albert Camus’ love of goalkeeping mirrors his absurdist philosophy. Finding rebellion, purpose, and meaning in football’s chaos, where futility becomes freedom and play defies despair.

1957, Stade Yves-du-Manoir. Racing Club de Paris vs Monaco.

Racing Paris’ goalkeeper allows a wayward cross into his near post and ignites a roar from the away end. The fans can just about see the action from across the racing track that surrounds the pitch. In the crowd are thousands of men, donned in waist-tied trenches and neck-tight ties, politely driving cigarette exhalation away from one another during conversation. Sat amongst these men is the most recent Nobel Prize (for literature) winning writer Albert Camus; beside him, an overcoat-wearing journalist.

The Journalist probes Camus with his microphone. “Racing’s Goalkeeper doesn’t seem to be in his best form…”

Camus’ eyes don’t wander from the match in wake of such a provocation, and, just as he’d likely been taught by the goalkeeping coaches of his adolescence, he keeps his eyes on the ball in play before responding:

“Don’t blame him. If you were in the middle of the sticks you’d realise how difficult it is.”

Camus’ understanding of the pressure that accompanies the goalkeeping position derives from a bout as one himself – a starting goalkeeper for the Algerian University Racing Club during the 1930s. He was considered a genuine talent by the RUA, and had a prolific flare in goalkeeping respect. However, during his sixteenth year, tuberculosis struck, rendering him unfit to play football indefinitely.

A year before his passing, some thirty years after his forced ‘retirement’ from football, the Nobel Prize winner had professed that the football pitch was just as much a university than any other educational institution. Raised in the slums of Algiers, he learnt as much from kicking a ball of rags with his fellow impoverished children than he did from the world around him – the character of Jacques in Camus’ The First Man is an autobiographical protagonist, exploring his youthful passion for the beautiful game. The fever of love that football inspires is one that is ever rife and ingrained into working-class cultures; a sense of community and purpose through the means of sport is an ancient phenomenon, evolving alongside those who perpetuate it.

Soon, the journalist realises that, perhaps, he may get more from Camus from enquiring about his recent success in literature.

“Which factors affected the Jury’s choice?”

Camus responds in a manner of which the culture of football demands of its players – respect, class, and humility. “I think there are a couple of other writers who should have been chosen before me.” Again, his eyes focusing on the match in front of him.

With Albert Camus’ legacy of an absurdist nature – one that urges the individual to reject both physical and philosophical suicide due to an implication of cowardice that comes with either option, it can seem contradictory for the writer to be such a devout fan of football; after all, to its many dedicated fanbases, the beautiful game is a way of life – not too dissimilar to a religion. The off-brand dedication is highlighted when reviewing Camus’ concept of philosophical suicide (which is to be found in his 1942 essay, The Myth of Sisyphus), or, the rejection of predetermined ideologies that offer ‘answers’ to the absurdity of one’s existence. Football is no different – at least in the context of the sport as a religion, or as a deity to ‘follow’ or learn from. As previously mentioned, Camus stated that he had learned everything there is to know about life from his days following football. By this, he is referencing cultural customs such as respect, loyalty, teamwork, passion, and determination – all significant sentiments of the footballing world. Whilst these are customs that are still a possible necessity for the Absurd Man, Camus’ hero who embraces life’s absurdities, the context of discovering them by means of subscribing to a subculture of footballing nature seemingly undermines Camus’ rejection of philosophical suicide. However, due to the age of which young Albert began his subscription on the streets of Algiers, it is equally as possible to overlook, for he, like many in their adolescent years, are susceptible to the culture that surrounds them.

Despite this possible contradiction, it is quite fitting that Camus opted for the goalkeeping position over any situated outfield. The lore of football states, more often than not, that the ‘goalie’ is, by far, the craziest player on the pitch. To have such a commitment to throw one’s body, sometimes for distances which are as long as the keeper is tall, requires a great acknowledgement of risk – both physically and mentally – an amount of risk for such a meaningless reward that only Camus’ Absurd Man would be comfortable with. Perhaps the thrill of the absurd is what attracted a young Albert to the goalkeeping position, or perhaps it was the game itself. One thing, however, is a certainty: if Camus wasn’t a goalkeeper, he would have never coined his own ideologies. As Jonathan Wilson, in a historical account of the goalkeeper’s development, professed – “The most influential opinion-formers have found a scapegoat: Marx blamed the capitalist system, Freud blamed sex, Dawkins blamed religion, Larkin blamed his parents and Dr Atkins blamed the potato. Footballers blame the goalkeeper.” The goalkeeper is the ultimate outsider; chained by a different set of rules to their teammates, they have perhaps the most important position on the field, where their every mistake inevitably leads to conceding a goal. Their voices are the loudest with a requirement to yell to their defence, and their skin is the thickest to withstand berating from the fans that stand no less than two meters behind them. The goalkeeper is a fully-realized beacon of independence, free to roam alone, and eager to dive into experiencing life’s absurdities with complete confidence.

With this in mind, there is a possibility that football isn’t contradictory to Camus’ philosophies, and that the game itself might be the perfect visual representative, besides Sisyphus, of Camus’ ideologies. Alongside his love for the outside nature of the goalkeeping position, the keeper’s context within the game that they are playing, makes for the perfect absurdist canvas. Twenty-two players, putting their pride, their physical health, and their local (sometimes international!) reputation on the line for the chase of a ball of leather; some win, some don’t, but in the face of adversity, they play again anyway, despite knowing their true skillset may be far inferior to their opponent’s – much like Camus’ analysis of Sisyphus.

The sheer love of what they do is enough to live for; the players laugh in the face of life’s absurdity and throw themselves at it with an immeasurable passion and dedication. Their rebellion, their refusal to commit either physical or philosophical suicide, is what is so attractive about football. Conclusively, it is in fact not philosophical suicide, for unlike a philosophy or a religion, it does not promise an answer to the meaningless of our existence, but it encourages its fanbases, club coaches, kit managers, and its players, to rebel in the face of absurdity.

Written by Oliver Bridges

Comments ()