“The Curse of Philosophy”, When Philosophy Causes Suffering - Learning From The Philosophers

The irony of philosophy and those who study it.

In this essay, I will focus on why I say philosophy is a curse. Why, throughout history, those who embraced philosophy ended up with miserable lives of death, ostracization, and even insanity, without gaining anything from their philosophy.

The topics of discussion are:

- Introduction of Philosophy

- Socrates & His Death

- Ibn Rushd & His Exile

- Spinoza & His Excommunication

- Kierkegaard & His Broken Heart

- Nietzsche & His Madness

- Conclusion & Lessons

Introduction to Philosophy

Philosophy, as we know it from various definitions, is a branch of knowledge that questions the essence of everything that exists. The word “Filsafat” in Indonesian, or “فلسفة / Falsafah” in Arabic, derives from the Greek word philosophia, which means “love of knowledge” or “love of wisdom.”

By definition, philosophy itself carries different meanings, depending on how each thinker interprets it. For instance, Aristotle defined philosophy as the science that encompasses truth, within which lie the disciplines of metaphysics, logic, rhetoric, ethics, economics, politics, and aesthetics.

Then comes Al-Kindi, who argued that philosophy is the knowledge of the true nature of things within the limits of human capacity. Since the purpose of philosophers in their theorizing is to seek truth, their practice must also align with truth. And, of course, there are many other interpretations.

Thus, based on the conclusion above, philosophy in essence possesses various meanings, and up until now, there has never been a single definitive definition of it. This is, in fact, consistent with one of its characteristics: absolute truth is utterly foreign to philosophy, never found nor fully known to this very day.

Yet the next question arises: does this beautiful definition mean that philosophy makes those who study and live within it surrounded by wealth, prosperity, and fame from the people around them?

Certainly not. Based on what I have learned from various literatures, the reality is the complete opposite. Why is that so? Because throughout the 2,500-year history of philosophy as we know it today, it was pursued by individuals who endured immense pain and suffering-suffering so great that we can only imagine the weight they bore.

Therefore, in this writing, I will explain the sorrows and afflictions of the philosophers we know today-those who did not merely think, but were consumed and broken by their very own philosophy.

Let us begin, and learn their story.

Socrates & His Death

Socrates, born around 470 BCE in Athens, Greece, and who died there in 399 BCE, was a philosopher renowned across the world-both in the West and the East-and is still remembered today as one of the most influential thinkers in the Western philosophical tradition. He is regarded as one of the few philosophers who permanently changed the very way philosophy itself is understood. At that time, philosophy was largely seen as the study of the universe, yet Socrates brought it into the realm of society and into every aspect of human life, especially within the sphere of community and ethics.

I personally regard Socrates as a fascinating and unique philosopher, precisely because he never wrote a single book or left behind a written work. Much of what we know of him comes from second-hand sources, namely his students such as Plato and Xenophon, who immortalized his name through their writings. Yet he is remembered as a controversial and courageous figure in the struggle to defend right and sound reasoning.

As found in one of Plato’s works I once read, Apology, the book narrates the brilliant defense Socrates gave against the accusations of his opponents. One of the charges was that he had “corrupted” the youth of Athens. In truth, however, this “corruption” did not carry a negative meaning; rather, it referred to how Socrates encouraged the youth to seek truth and resist being deceived by the rulers of the time.

In the end, after numerous accusations, Socrates lost in court and was sentenced to death. As we know, he accepted his punishment with serenity, even though many had offered to help him escape.

In Apology (p. 88), he is recorded as saying: “Stay a little longer, my friends, so that we may talk with one another while there is still time before I depart this world. For what I do now is solely to show that what I have done is not evil, and also to prove that the belief that death is evil is not true.”

Ultimately, he passed away, leaving behind an invaluable lesson for us across the millennia: that to think rightly-especially when it threatens the power of rulers-may lead to death, and that truth itself often brings exile and suffering to its defenders.

Ibn Rushd & His Exile

Ibn Rushd with his real name: Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad bin Muhammad, born on April 14, 1126, in Córdoba, Spain, and who died on December 10, 1198, in Marrakesh, Morocco, was a polymath and one of the greatest philosophers in the Islamic tradition. He was also a fundamental source of thought for post-classical European philosophy. His philosophical works included numerous commentaries, paraphrases, and summaries of Aristotle’s writings, which earned him in the Western world the title “The Commentator.” Among those influenced by him was Thomas Aquinas, a central figure of the scholastic tradition.

In Islamic history, Ibn Rushd is remembered for defending Muslim philosophers such as al-Farabi and Ibn Sina, who were widely regarded as heretical by many theologians and the general public. This defense is most clearly expressed in his most famous and controversial book, Tahafut al-Tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence), in which he refuted the accusations of unbelief that al-Ghazali had made against the philosophers in Tahafut al-Falasifah (The Incoherence of the Philosophers).

Ibn Rushd was close to the Almohad dynasty’s ruler of his time, especially Abu Yusuf Ya‘qub al-Mansur, the third Almohad caliph. Because of this close relationship, Ibn Rushd was granted a high position as qadi al-qudat (chief judge). Yet this prestigious role aroused resentment among jurists who disagreed with his views. To bring him down, some of these jurists fabricated charges against him, accusing him of spreading a philosophy that deviated from Islam.

As a result, Ibn Rushd was exiled to a place called Lucena. His philosophical books were burned, and an official decree was issued forbidding the study of philosophy. From that moment on, philosophy was deprived of its rightful place in the Islamic world, its intellectual grandeur suppressed in the name of religion. Some years later, al-Mansur pardoned him and released him, after which Ibn Rushd went to Morocco, where he spent the remainder of his life.

From this, we may understand that Ibn Rushd did not teach heresy. Rather, he called upon us to use our reason and not to hastily declare others as unbelievers without proper verification. Yet because of false accusations by literalist scholars, he was ultimately exiled for his thought.

Spinoza & His Excommunication

Baruch de Spinoza, born on November 24, 1632, in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and who died on February 21, 1677, in The Hague, is remembered as one of the major philosophers whose ideas would profoundly influence the Enlightenment. Spinoza’s thought contributed significantly to the rise of modern biblical criticism, seventeenth-century rationalist philosophy, and contemporary conceptions of the self and the universe.

Spinoza is regarded as one of the most important and radical philosophers of the early modern period. This is not surprising, for in his writings he denied the immortality of the soul, firmly rejected the notion of a transcendent and providential God-the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob-and claimed that the Law (that is, the commandments of the Torah and the principles of rabbinic jurisprudence) was not literally given by God and was no longer binding upon the Jewish people. These ideas led, on July 27, 1656, to his being served with a herem-the most severe form of ban, prohibition, or excommunication ever pronounced by the Sephardic community of Amsterdam. This ban was never lifted, and he was accused of teaching heresy.

In one of his works that I have read, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, Spinoza does not, in fact, promote heresy. Rather, he opens our understanding of God and religion, for example, by showing that the structure of the Bible is in essence a text compiled from multiple authors and diverse origins. He also strongly rejected the Jewish idea of “chosenness,” arguing instead that all nations are equal, for God does not elevate one above another.

As we can see, his thought led to his being cast out by his own Jewish community and denounced as a teacher of heresy and innovation. Yet in later generations, as Rebecca Goldstein described, he would be remembered instead as “a Jewish rebel who gave us modernity.”

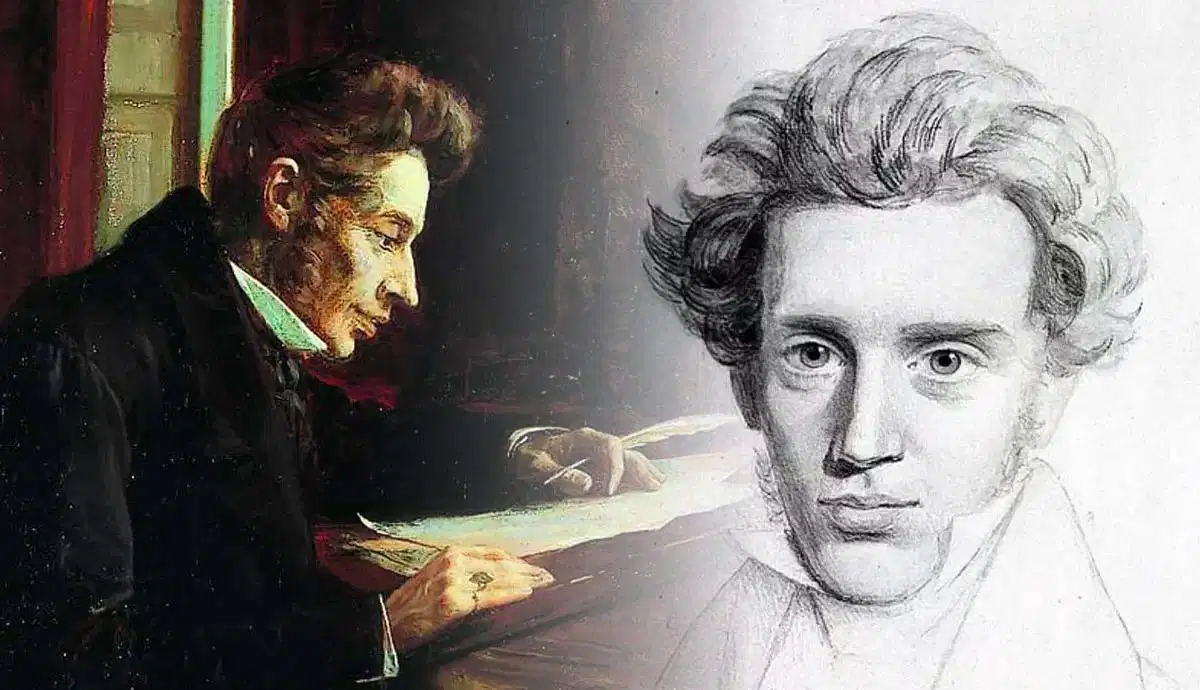

Kierkegaard & His Broken Heart

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard, born on May 5, 1813, in Copenhagen, Denmark, and who died there on November 11, 1855, was a nineteenth-century philosopher and theologian known as the father of existentialist philosophy. This title is due in part to his central concern with the question of what it means to be a finite, existing human being-a concern that he associated with “inwardness,” and which stood in stark contrast to what he considered the mistaken belief that reality could be understood apart from a particular perspective.

In 1840, Kierkegaard became engaged to Regine Olsen, who was eighteen at the time. Soon after the engagement, however, he realized he had made a great mistake and could not marry her. His reasons remain uncertain but have long been the subject of speculation, most often relating to Kierkegaard’s own “melancholy” and his complicated relationship with his late father. In returning her engagement ring, he asked for Regine’s forgiveness, confessing that he was “a man who, whatever he may do, could never make a girl happy” (quoted in Hannay 2001: 155).

In his journals, Kierkegaard reflected on this decision years later, remarking that within six months of marriage, Regine would have been “utterly shattered,” for there was “something spectral within me” that would have made a “true relationship” impossible. Unsurprisingly, Regine resisted the breaking of their engagement. Nevertheless, a year later Kierkegaard brought it to an end, and some years afterward Regine married Johan Frederik Schlegel-an event that deepened Kierkegaard’s heartbreak.

From this, we may see that Kierkegaard felt called to a “spiritual mission” that demanded personal sacrifice. He was also acutely aware of his inner darkness, often writing of the “burden of spirit” he carried in the form of melancholy, guilt, and a tragic consciousness of existence. Believing that he could not provide a woman with ordinary happiness, he released Regine.

Here we learn that deep reflection on the nature of the self can break one’s heart; for in looking inward, one may also encounter one’s own darkness. Yet out of this great sacrifice, Kierkegaard produced works of profound influence that have endured long after his death.

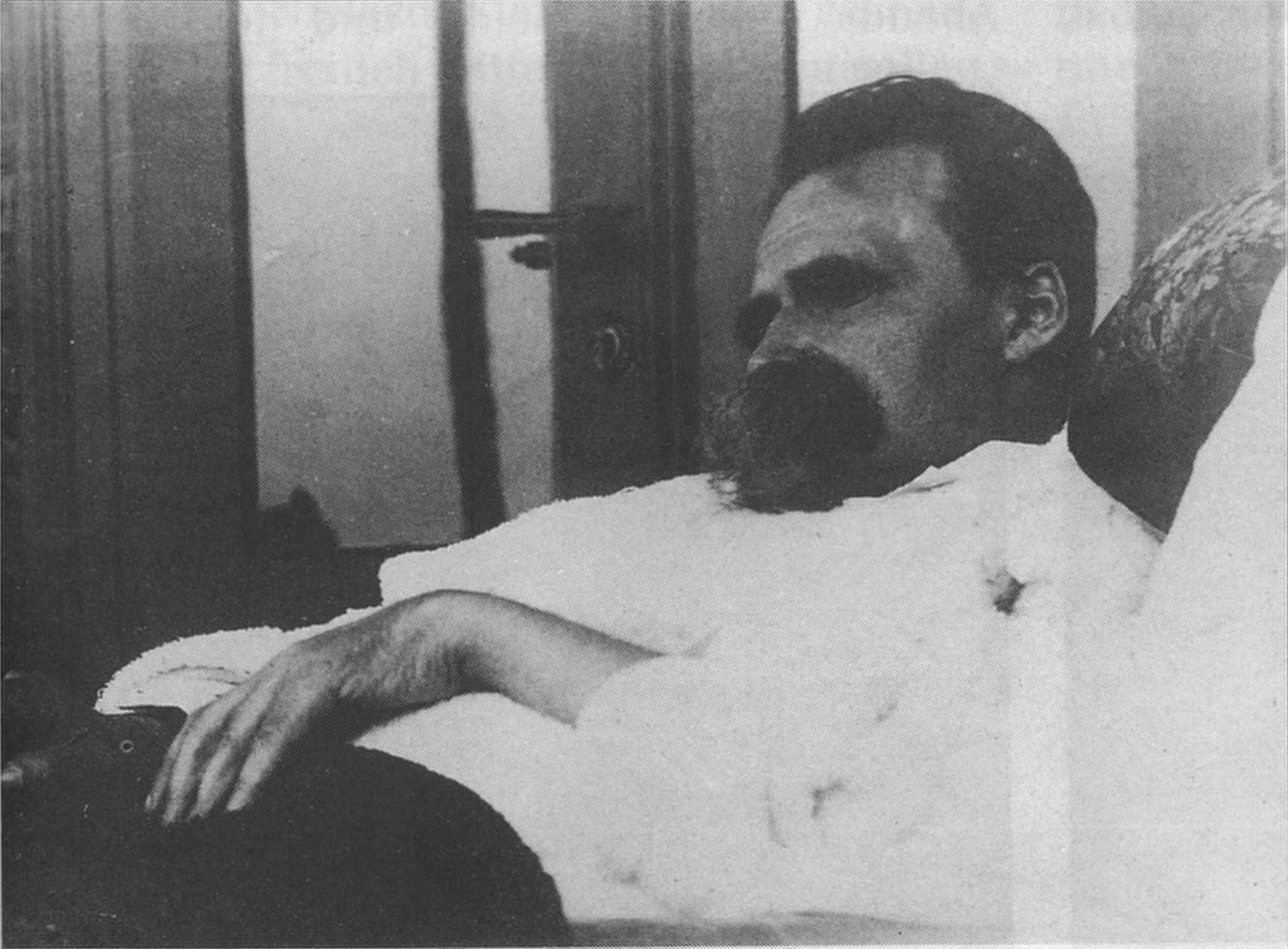

Nietzsche & His Madness

Friedrich Nietzsche, born on October 15, 1844, in Röcken, Lützen, Germany, and who died on August 25, 1900, in Weimar, Germany, was a philosopher renowned for his uncompromising and sharp critique of traditional European morality and religion, as well as of conventional philosophical ideas and the social and political pieties associated with modernity.

Among his many critiques, Nietzsche is perhaps most famous for his assault on traditional European moral commitments and their Christian foundations. His critique was wide-ranging: it sought to undermine not only religious faith or philosophical moral theories, but also many central aspects of everyday moral consciousness-such as altruistic concern, guilt for wrongdoing, moral responsibility, the value of compassion, and the demand to treat all people equally.

In my view, Nietzsche’s thought was driven by his radical questioning of truth itself. He believed that religion had already lost its authority, for by his time many European intellectuals assumed that however inspiring the Christian tradition had been, its ideas required rational foundations independent of sectarian or even ecumenical faith.

From this critique of religion and its truth-claims arose one of his most extraordinary ideas, found in his major work Thus Spoke Zarathustra: the concept of the Übermensch. This was an ideal for humanity, a goal consciously set by human beings for themselves, grounded in values they themselves created. Nietzsche envisioned the Übermensch as a replacement for the moral framework of religion, which in the modern age had lost its power under the advance of science and technology.

Yet in the story of his life, we see that Nietzsche himself failed to embody the Übermensch. He ended in madness-not merely in the medical sense, but in an existential sense. For it is nearly impossible for human beings to establish absolute values wholly apart from religion, since religion conveys not only truth and goodness but also the dimension of faith-something that cannot simply be replaced by inventing new meanings.

From this we learn that while we may not fully agree with Nietzsche, he teaches us a profound lesson: that philosophy can end in madness. And through one of his most famous proclamations-“God is dead,” or in German Gott ist tot-he indirectly reminds us that many people who claim to follow a religion do not live by its teachings, thereby removing God from their hearts, minds, and actions.

Conclusion & Lessons

From the discussions above, we can understand that merely engaging in philosophy does not necessarily make us widely accepted by others. Even though philosophy, in its truest sense, invites us to think correctly and to become wise, many people dislike such pursuits.

As we know, many still prefer to live in illusions rather than face reality, and many choose to dwell in false comfort and wrongdoing rather than confront the painful truth.

Yet, from the sacrifices made by the philosophers mentioned above, we are left with an extraordinary lesson, namely:

“The courage to think independently - even when the cost is death, exile, rejection, heartbreak, or madness - gives birth to timeless ideas that endure through the ages.”

About The Author: Abiyyu Fayyadh

"Abiyyu Fayyadh, also known as Abu al-‘Abbas Muhammad Umar al-Fayyadh, is an interdisciplinary thinker in philosophy, theology, law, and AI. He is the founder of The Commentator, Strategic Advisor at The Stars & Stripes Battalion, and a writer at THELIFTEDVEIL. With over four years of higher education expertise, he draws on classical Muʿtazilite rationalism while engaging modern philosophy, mysticism, science, and technology. His vision is to harmonize reason, revelation, and ethical innovation into a coherent system for a just and spiritually grounded future."

References

[1] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Philosophy.” https://plato.stanford.edu/search/searcher.py?query=Philosophy

[2] Ensiklopedia Islam. “Filsafat.” https://ensiklopediaislam.id/filsafat/

[3] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Socrates.” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/socrates/

[4] Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Socrates: Life and Personality.” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Socrates/Life-and-personality

[5] Plato. The Apology of Socrates. Translated by A. Herlianto. Yogyakarta: CV. Indoliterasi Publishing House, 1st ed., 2023.

[6] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Ibn Rushd (Averroes).” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ibn-rushd/

[7] Ensiklopedia Islam. “Ibnu Rusyd.” https://ensiklopediaislam.id/ibnu-rusyd/

[8] Nadler, Steven. Spinoza: A Life. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed., 2018.

[9] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Spinoza.” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/spinoza/

[10] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Kierkegaard.” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kierkegaard/

[11] The Collector. “Who Was Søren Kierkegaard?” https://www.thecollector.com/who-was-soren-kierkegaard/

[12] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Nietzsche.” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche/

Comments ()