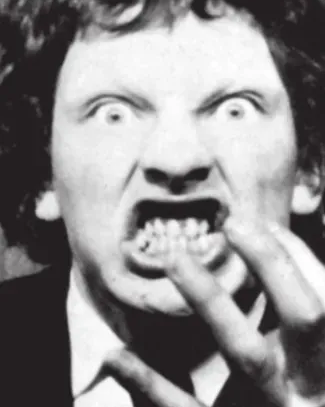

Beneath clinical labels the human animal remains untidy, volatile, and haunted. These lives show how alienation curdles into control, and control into ritualized ruin.

INVESTIGATIONS

UNVEILING DEPTH. CHALLENGING PERCEPTION.

Beneath clinical labels the human animal remains untidy, volatile, and haunted. These lives show how alienation curdles into control, and control into ritualized ruin.