A stark exploration of how memory, obsession, and poetic, scientific, and psychotic quests can unthread our grip on reality, pulling perception into madness.

Read next

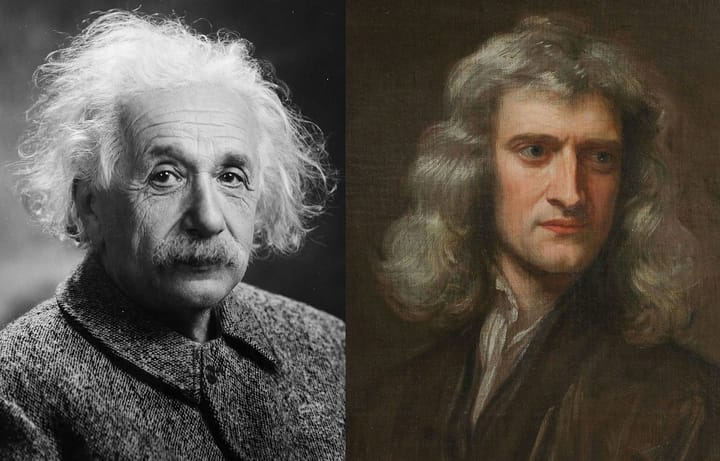

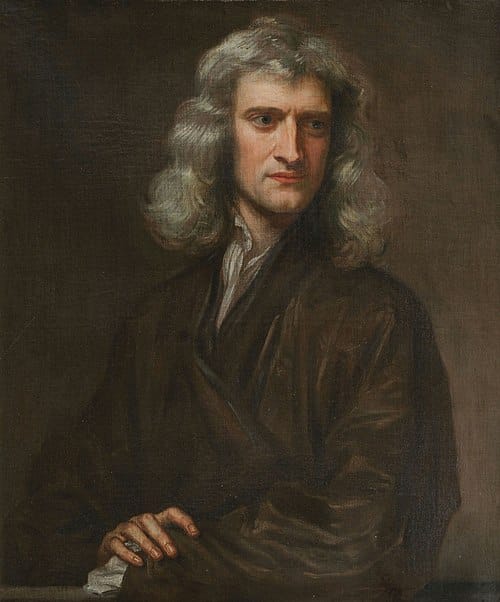

On Einstein and Newton

A comparative meditation on how Einstein and Newton. Two unmatched giants of physics rose to genius through entirely different lives, pressures, and intellectual temperaments.

The Birth of A New Image of The World

This essay explores how the fall of Newtonian physics and the rise of Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics transformed our understanding of scientific truth, revealing that no theory is ever final.

Between the Science of Philosophy and the Act of Philosophising

Distinguishes the Science of Philosophy from the act of Philosophising, exploring study versus lived reflection in thought, action, and inquiry.