The graveyard is humanity’s last illusion, a monument to our refusal to accept impermanence. Only by internalizing death as life’s quiet companion can we evolve beyond our need to carve permanence into the earth.

Read next

On 764 as A Clinical Ontology of Digital Collapse

764 is not a cult of belief but a system that organises collapse by rewarding visibility over recovery and recognition over care.

AGI And The Race To Extinction

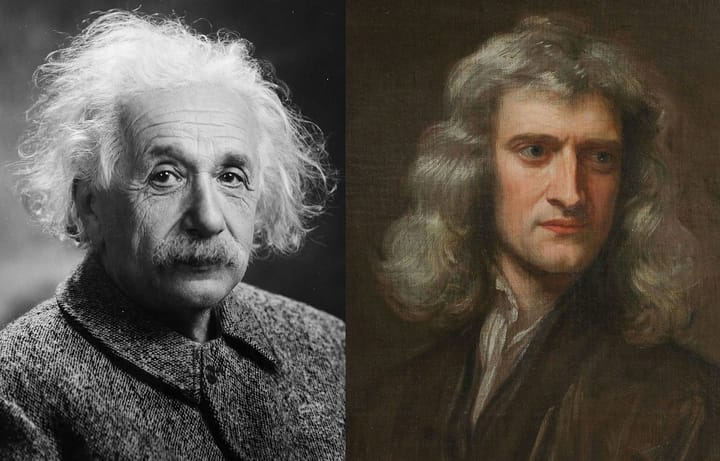

On Einstein and Newton

A comparative meditation on how Einstein and Newton. Two unmatched giants of physics rose to genius through entirely different lives, pressures, and intellectual temperaments.