Against Human Rights

The Criticism of Human Rights

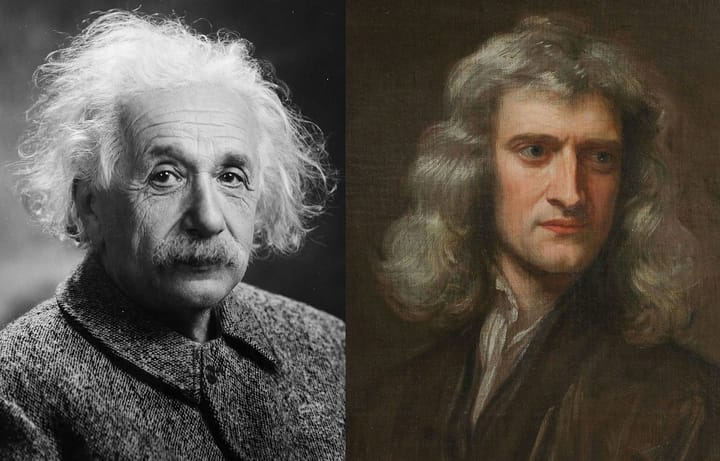

There is a line of philosophy, born from that of classical liberalism, which at the very least has been championed in name and has dominated since then throughout the world. I speak on the idea of human rights, and while the idea has its merits, it is a philosopher's duty to show the limits of an idea, its practices, and what it could possibly mean. But before the torches and pitchforks are raised, this is not born out of an immoral objection to human rights but, nevertheless, is a criticism and objection of what they are. In this essay, I will merely attempt to revive the two similar arguments that come from two of the greatest philosophers of recent times, and what they stand for on the matter will be made crystal clear later. My own questions, provocations, and criticisms will be made briefly after theirs. For now, let us get an idea of what human rights are.

Based off of John Locke's (1690) unalienable rights, which included life, liberty, and property (or the word used is 'estate'), what can be called human rights are largely based off the modified version of Locke's ideas that come through the Declaration of Independence, à la Thomas Jefferson, and they are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Notice how it is the pursuit of happiness and never happiness itself, a glimmer of wisdom from the founding fathers. Although in today's world, these unalienable rights have been somewhat expanded to mean a plethora of things, for instance, there now is the widely accepted human right to clean water (as the UN once held a vote in recognizing the right, which the United States abstained from voting) and the right to food. And while these are noble sentiments in themselves, one of the problems that becomes immediately apparent is the fact that human rights, despite often coming with the label of unalienable, meaning that they cannot be taken away, are not really clear in what they suppose at all and are very much still subject to powers like the state (government), as well as other, more serious, covert issues and baggage.

This, as well as more central problems to the matter, did not go unnoticed in the 20th century by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze (1996), who once said in a series of transcribed interviews that:

The reverence that people display toward human rights— it almost makes one want to defend horrible, terrible positions. It is so much a part of the softheaded thinking that marks the shabby period we were talking about. It's pure abstraction. Human rights, after all, what does that mean? It's pure abstraction, it's empty. It's exactly what we were talking about before about desire, or at least what I was trying to get across about desire. Desire is not putting something up on a pedestal and saying, hey, I desire this. We don't desire liberty and so forth, for example; that doesn't mean anything. We find ourselves in situations. (para. 1)

Taking inspiration from a thinker that will be discussed later, Deleuze continues while invoking discussion of the Armenians and the bloodshed by the Turks during the Armenian Genocide, as well as the 1988 Armenian earthquake. And what he says specifically about the violence itself is striking and enlightening:

That's not a human rights issue, and it's not a justice issue. It's a matter of jurisprudence. All of the abominations through which humans have suffered are cases. They're not denials of abstract rights; they're abominable cases. One can say that these cases resemble others, have something in common, but they are situations for jurisprudence. (para. 4)

What Deleuze is doing is transforming the ball game; he is, in fact, changing the field so he can rightfully point out the common discourse of human rights in general, and in particular, he says that "the Armenian problem is typical of what one might call a problem of jurisprudence. It is extraordinarily complex " (para. 5). And with the final piece of the puzzle, we can stitch together his proper attack on human rights. In the same paragraph, he adds:

To act for liberty, to become a revolutionary, this is to act on the plane of jurisprudence. To call out to justice – justice does not exist, and human rights do not exist. What counts is jurisprudence: *that* is the invention of rights, invention of the law. So those who are content to remind us of human rights, and recite lists of human rights—they are idiots. It's not a question of applying human rights. It is one of inventing jurisprudences where, in each case, this or that will no longer be possible. And that's something quite different. (para. 5)

Deleuze's attack on the idea of human rights is partially straightforward: firstly, if I am to understand Deleuze, jurisprudence is not the jurisprudence known in the Anglo-American sense; it is not a stuffy legal theory or legal philosophy, as there is a mode of practicality within it; it means to take action and examine things case-by-case. It is highly tailored to the context of the issue, and this can be gleaned in Deleuze's words when he mentions that the Armenian problem, specifically, is extraordinarily complex. The French jurisprudence takes action, and Deleuze's notion encompasses both action and a deep understanding of the context in this circumstance—that is to say, it does not refer to what seems like a rigid body of law and accept its answer, and though it may incorporate loosely some of these elements, it still too remains practical. Thus, his very first attack on human rights is that these abstract ideas have, in fact, gotten in the way of practicality, and this is because many (including odious intellectuals) use the idea of human rights to throw a blanket on many complex topics and call it a day. Is it all that helpful to ignore the specific context of a situation, mutter a list of violated human rights, and move on? Is it any wonder that Deleuze calls those that recite the lists idiots? What this does is no justice in the practical, nor does it seek to properly understand the context of highly complex issues. It, in a fashion, covers up complexity by instead prattling on about potential violations, and nothing is done. He says that a right and the law are inventions from jurisprudence; jurisprudence is their source, and not the other way around. In other words, action and understanding are of the first order, and human rights never manage to break through to it. And Deleuze is not finished yet, as he finally says:

Human rights—what do they mean? They mean: aha, the Turks don't have the right to massacre the Armenians. Fine, so the Turks don't have the right to massacre the Armenians. And? It's really nuts. Or, worse, I think they're hypocrites, all these notions of human rights. It is zero, philosophically it is zero. (para. 10)

What does it mean to say that one doesn't have the right to take another's life? Does that somehow stop it from happening? What does that do? It seems as though, really, and in the example, it doesn't matter if the Turks did or did not have the right to take the lives of the Armenians—they would have done so regardless, and to say they do or do not have the right to do so means nothing because at a point, human rights are abstracted from reality. For Deleuze, human beings find themselves in situations, and we use jurisprudence, that is to say both the plane of action and analysis, to deal with them as they come. Human rights almost take the wants and desires of their desirers and nearly misplace them. By that same token, how foolish would it have been to say that a Hitler or a Pol Pot did not have the right to kill millions? Or how about the other flagrant violations of human rights done by governments around the world? What does this exactly do besides act as a moral condemnation—it does not change the past nor present—it means absolutely nothing, philosophically zero.

And the attack on human rights does not belong exclusively to Deleuze, nor is Deleuze's strongest point even his, as this is where he borrows from Max Stirner (1844/2017), perhaps the most unique einzige that has ever lived. Stirner might have actually been the first on record to point out the fatal flaws of human rights. For him, they were nothing more than spooks, phantasms, and abstractions—that means they were nothing more than very abstract ideas instead of what was in the here and now, the concrete. And he carefully noticed how the egoist (and everyone is an egoist/unique, but most are not yet fully realized) gives power away when they put such ideas above themselves, the totally unique or egoist, for lack of a better word. In particular, Stirner makes vicious attacks on human rights, but not merely just them:

But only I have everything that I get for myself; as a human being I have nothing. One wants to let everything good flow to every human being, merely because he has the title "human being." But I place the emphasis on me, not on my being human. (p. 194)

The place this comes from is not some feel-good house of morals but from how abstractions, like human rights, become divorced from the "me", "I", and the "unique". In other words, what you are and who you are, not a "human being" or "mankind", which he felt were in the same boat of spooks. Similarly, what Stirner says about freedom is equally applicable here:

If you reflect on it correctly, you don't want the freedom to have all these fine things, for with this freedom you do not have them; you actually want to have these things, to call them yours and possess them as your property. What use is a freedom to you, if it contributes nothing? And if you became free from everything, you would no longer have anything; because freedom is lacking in content. (p. 170)

Is it not true that when Stirner speaks on freedom, he also is speaking on what the majority believe are human rights? The human right to clean air, water, or food, to not be killed by authoritarian regimes? These are freedoms that are unalienable, guaranteed to every human at birth—in theory. But is it not also true that when you are thirsty, you do not want the right to water; you want the water itself. What are then the uses of these freedoms and rights when they are roundabout, and these days, terribly bureaucratic, abstractions that never actually guarantee a single thing? The rights to something are not the same as having that thing, and it is worth mentioning that freedom to Max Stirner is seizing that very thing, creating one's own freedom as a unique/egoist. That is a kind of freedom no government, institution, or anyone else can promise: it is a freedom that only you can make for yourself, and no one else!

Deleuze and Stirner do not babble, and only once one takes the time to really examine what human rights are, their prejudices, and their limits, can it really lead to the thinking that perhaps there are better methods and fashions for changing the world, even through the typical humanistic lens many advocates for human rights have. As a philosopher, my own view owes much to the likes of Deleuze on the matter, and especially to that of Stirner, a prime inspiration for my own thinking. I ask, what determines the shifting nature of these rights? And also, if the domain of human rights has indubitably grown, if we are to take them seriously, are some more legitimate than others? Who decides? And how are rights "enforced" or characterized? When a duty is ignored, as some interpreters of Locke view rights, for instance, the duty fails. More importantly, what do they matter if these pretty ideas are still subject to abuse by powerful institutions? When a government can just ignore them and pay them no special interests? What then are they now but novelty little trinkets that at one time helped topple kings and now sit quietly on the shelves? Or worse: the language of human rights is now used as a stalking horse for oppression, economic domination, and imperialism. And it is easy to see how, "Of course we can invade that country; their government has no regard for human rights, but we are arbiters of freedoms, rights, and democracy. We would be doing them a favor by liberating them." What do abstract rights say in regard to that? Their mouthpieces? Or do they remain silent until the time comes for them to sing their single tune? Stirner went after the truly empty content of rights in themselves, and Deleuze was correct to point out their critical usage, as they fail to touch the real world of action, and he did this while borrowing Stirner's critique (or perhaps, in Stirner's language, made it his own).

It goes to show that to a philosopher, there ought to be no sacred ideas, everything must be looked at and checked lest they become a dogma—a fixed, sacred, and relatively untouched idea is perhaps the one that needs to be examined most. If that is so, then human rights, what they could potentially mean, and what they actually do once again need a pair of critical eyes. For the philosopher is the exception, and they must necessarily point out what has been overlooked, where, and what can be done better. Deleuze's cry for the philosophical worthlessness of rights may be overstated, but at the very same time, if one ever wishes to salvage rights, they need to deal with its criticisms, criticisms that split the holy lock of the people's chest of phantasms and sacred ideals. Thus the case against human rights stands strong, no matter how hated.

References

Deleuze, G. (1996). L'abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze: On human rights (paras. 1, 4, 5, 10). Retrieved from https://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Phil%20108-07/Deleuze%20on%20Human%20rights.htm (Original interview in 1988).

Locke, J. (1690). Two treatises of government: Second treatise of government.

Stirner, M. (1844/2017). The unique and its property (Wolfi Landstreicher, Trans.). Underworld Amusements (pp. 170, 194). (Originally published in 1844)

Notes

For further reading on the comment regarding the UN vote and U.S. abstention: undispatch.com/why-the-united-states-did-not-support-water-as-a-human-right-resolution

For further reading and a different translation of the statements of Deleuze on human rights: https://deleuze.cla.purdue.edu/lecture/lecture-recording-2-g-m/

Comments ()